There is no other way around it. My sweetest dad will no longer be making another cup of tea, wearing his slippers again, painting another picture, singing another song, dreaming another dream. His clothes still smell of him. They are still hanging by the door. The way he left them. His shoes too, with the socks rolled in them. His turban still retains some of its shape from when he wore it last. Yesterday I found how my mother had placed his summer clothes in his closet, like any other year after the end of winters. His toothbrush is in the stand. We are still using some of the grocery he last bought. I have taken to brushing my teeth regularly at night, switching off extra lights around the house, cleaning my mother’s car in the morning in his place and watering the plants. It soothes me like nothing else. In that moment, I am him. His clinic is the same. His glasses are still on the table, his last signed medical prescription for a patient, open. I feel his presence but I want him to talk back. There is no way around it. I feel like for the first time in my life, I have been completely cornered. That no amount of hard work or prayers, anger or love, can bring him back. Lately, I have been thinking of time machines and resurrection. Parallel universes. Not kidding. I am serious. I want to be an exception but everything screams that I am not. There is no way around it.

I have tried talking about him. Especially to him. I feel he is the only one who can help. Can you believe that? Only his help will do to deal with his absence. One night before my flight after I got the news, I almost called him to ask if I needed to keep any medication to deal with claustrophobia on the plane. For some reason, he always kept packing extra ORS packets for us all. I remember joking about it a week before he passed away.

We have a mango tree growing outside our home. During the lockdown, he was always taking pictures of its blossoms. This year too, he was so excited about the mangoes. Even now, as I write and look outside the window, the trees and plants seem to embody him more than anything else. This year, no one managed to pluck out the loquats. I saw squirrels with their tiny hands and birds with their small beaks biting into them. I knew he wouldn’t mind. Even before, he always left some loquats and mangoes hanging for them.

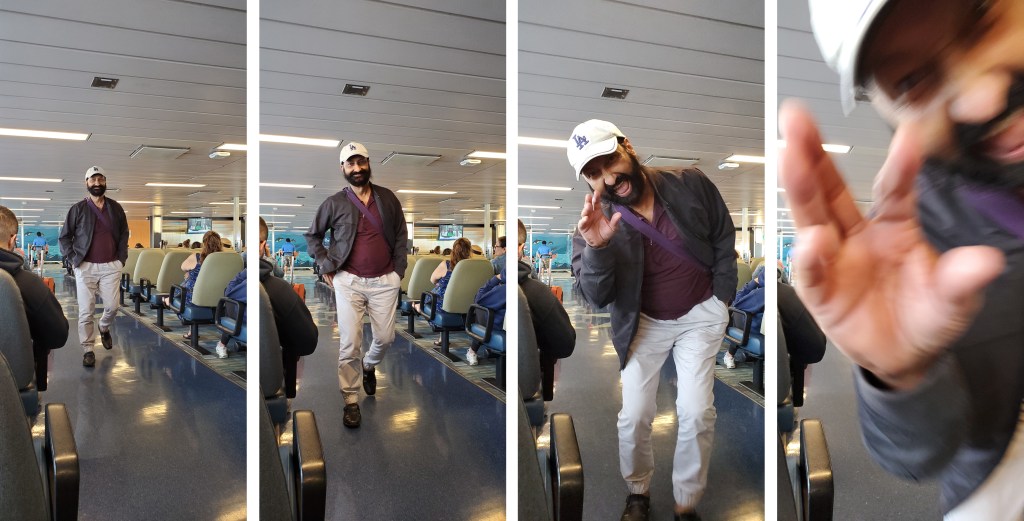

My father and I are/were different in so many ways. He was the life of the party, I see people and run in the other direction. I like to read, he didn’t. He wanted onions in his omelet, I don’t. He mixed ice cream with Gulab Jamun, and I don’t even know where to start with that.

But our souls are made of the same stuff. And though past and present tense divide us now, we continue to co-exist.

And sometimes, when I look closely at my hands, I see his hands there too.

Yesterday, while attending a meeting, I caught myself doodling and ended up drawing the first flower that my father had taught me how to draw, years back. I had not forgotten it. Four pink petals shaped like hearts around a circle. Even now when I think about the time I got angry at him for entering my room during an online meeting or got irritated with him for not understanding the simplest function of his new phone, I feel that even then my mind had stored away the memory of that first drawn flower somewhere. I just wish I could have remembered it sooner.

I recall how there was always fruit in the fruit basket on our dining table. I remember how he would come back from the office, hang the car keys by the door and put the fruit on the table which he would cut in the evening and place before us—me, my brother and my mother engrossed in a serious study session. Mostly only my mother was engrossed. We never failed to send a distress signal to dad to save us from mom’s fury that would inevitably erupt at any moment.

I remember those sunny winter days, how my father would bite off chewable pieces of the sugarcane for me and my brother. Sometimes it was oranges sprinkled with salt. Less popular was his method of splitting the banana with a knife covered with salt that would start oozing. He loved dozing under the winter sun, covering his eyes with his parna, his feet moving of their own accord at the slightest disturbance. We giggled uncontrollably at that.

As a kid, the sound of his scooter never failed to make me run to the gate, joyous that he was back. Later in life, he did not mind driving my pink scooter. Or using my old study table covered in stickers for his clinic. Or my old poster-covered closet. He was still making use of old sweet boxes to store his paint brushes. He was always utilizing what he had at hand. He even devised a way to pluck out the fruit without damaging the trees using old plastic bottles. Made a painting on blank backs of wedding cards, used old boards to create shelters for baby birds to save them from the stormy weather, made his own easel. We rarely had to call a carpenter or an electrician. He took pride in doing things on his own, silently, before a problem became apparent.

Silently too, he held the invisible burden. We did not see it. He was always behind us. Always out of sight but elemental. Our backbone.

The house too is falling apart now, without him.

I never thought he paid so much attention to what we said, offhandedly. In Canada, we usually get milk in cartons. I had forgotten about milk packets. During the course of making endless cups of tea for everyone recently, I learnt that my father always told my mom to cut the milk packets diagonally. To never cut off the tip because of what I had told him years back about the environmental concerns that could cause. And I had forgotten all about it myself. I had also told him to buy frames that opened from the back so that he could rotate paintings he wished to display every season rather than getting them all framed. He had told me they did not sell those and the ones available online were too expensive.

And there they were, incomplete wooden frames, sheets of glass still neatly wrapped that we had to send back. He was actually thinking about making them on his own! And they were looking so good. We kept the frames. There is this one painting that he made and framed fully by himself which he placed in the clinic. Now it lies at my mother’s dresser. She looks at it daily while getting ready for work. Once she asked him to paint some purple tulips for her, purple being her favorite color. We found the footage on the CCTV camera, of my father drawing something a day before. We found it later, a canvas, hidden behind the other completed paintings, meant to be a secret project. A pencil sketch of tulips. Flowers, without color.

I see it now, my father’s growth as a painter. From his painting from the initial days that is taped to the wall of our washroom to his most recent one that was still on the easel, the blue sea, the paint not even dry that got on my hands later as I was clearing his art supplies— I can see how we took his growth as an artist so non-seriously. And how he stayed with it. Kept painting. Through hours of loneliness.

Hours. Precious hours. That I could have talked to him in. Shared all that now haunts me.

But you see, I never could see him as an artist. To me he was dad.

So I love his painting pasted on the washroom wall as much as his last.

Last time, when he came to visit me, he was pensive. His knee had been troubling him. Just when he had the time to finally take long walks through the forest trails or at the beach, his legs were giving way. I sensed he was depressed and coaxed him. You are the youngest of five siblings, why are you so worried about growing old?

Looking back now, my mother thinks he knew.

I have a new winter jacket lying in my closet to keep him warm in Canadian winters. There is a new backpack with the tag still intact that I asked him to buy for traveling. There is a bag half full of clothes and things my parents were planning to use when they came to visit me and my brother. That unfinished painting of tulips that my father left behind. Packs of his favorite granola that he bought only a few days back.

If you ask me if he knew he would be gone so soon, I would say I don’t think so.

When our parents came to visit me and my brother in Canada, we were so vigilant. It seemed as if our roles were suddenly reversed. We guided them with everything, being more familiar with the country even though my father was more well-travelled than us. We hushed them when they spoke too loudly over the earphones in the bus, listening to old Hindi songs. We reprimanded them if they walked on the wrong side of the aisles or hesitated while crossing the road when the green light turned to a countdown. We chose the best time and place to buy fruits. Once, my mother broke down into tears because we told dad not to buy apples even though he had carefully handpicked the apples he wanted to buy and had placed them already in a bag. They felt it deeply. I was careful after that one incident to tread sensitively around their feelings. I began to care less about what other people would say or think. Later that year, I called dad and told him how my brother and I rode a chair home, taking turns to sit on it, pushing it down the road outside. I remember my father laughing and saying that he was so glad we were finally comfortable enough in that country to do that.

He was back in India when it happened. But for the months he lived with me in Canada, I remember him cooking for me, making roti with sabzi, waiting for me to be back from work and spending that time painting. And even when I was home with him and it was time to eat lunch, I took mine to my room so I could watch something I liked while he watched news or saw videos on his phone. I did that all the time. Why didn’t I sit with him more often? Why didn’t I eat with him more often or talk to him? Why didn’t I hug him more often?

Why didn’t I tell him I loved him more often?

Sure, I thought I had all the time in the world. But would even a 100 years be enough?

These days it is winter indoors and summer outdoors. It rains a lot too lately. Every time it rains and the breeze floats in, I miss him terribly. I know how much he relished this weather. How he had a song for every rainy day.

I ache for him when anything beautiful comes my way. I am almost grateful for the pain knowing that he will not feel it.

My father used to wake up at 5 in the morning

Smelling of muscle pain sprays and toothpaste

Covered in pads, bands and appendages of varied kinds

He went and brought back home sweat, energy

And hardened hands from playing volleyball.

My father showed me his chipped tooth

His bone injury, his finger deformities, like relics

Others with bellies like pouches, came to play,

Bringing dogs and laughter, and complaints

And I wonder what my father said in return

And though I was old enough,

My father woke me up daily

With the warmest glass of milk.

Now in lockdown,

My father wakes up at 9 to workout

His clinic has turned into an art studio

Of which come daily a stream of songs

And celebrity sketches

That he uploads on Instagram

(I showed him how)

Throughout the day, he finds nooks and corners

That need fixing

And paints discarded yogurt containers

For growing money plants

The house turns greener and the mangoes grow

Unsaid he waters all the pots and trees

Listening to the radio in the kitchen

He makes the best cup of tea

Without fail

Every evening, no matter how hot it gets

He goes to the terrace and brisk walks

And plays tennis with the wall

The house rings with the sound of the ball

And the songs grow sweeter

With the summer smelling of mangoes.

After his retirement, my father always waited for my mom to have the evening tea together. Around 4:30, he would start pacing near the gate, sometimes watering the plants. He opened the gate before her car was even in view. Taking my mother’s lunch bag in his hands, he ushered her in, listening to her narrating how her day was. Then he made tea. He loved making tea with jaggery in it. I still remember his singing voice wafting from the kitchen. The tea box is still there. Opening any containers that he had last closed makes her break down and cry. For my mother, coming back home from work is the hardest. When she walks to her car, she is no longer thinking about retiring this October to finally have some time to spend with dad. Sometimes, I call her on her way back from dad’s phone. It seems to comfort us both in some way.

Yesterday, I saw all of my old identity cards from school days, neatly packed in my father’s almirah. A note about my first school day. My first day at my job. My childhood drawings were still pasted outside the almirah. I found a list of films he had recently watched and his to-watch list noted in a diary. A list of hashtags and instructions to download his karaoke songs that I told him about on the phone. Two days before he passed away, he messaged me on WhatsApp. It was a regular cleaning day at my home. My mother and father were thinking of renting out the upper section of our home. My father sent me the picture of an old doll’s shoe, covered in dust. He wrote, “Ruhi, your doll’s shoe.” Like some of the other messages he had sent, I glanced at it briefly and forgot to reply. Two days later, I got a call that he had passed away from a sudden cardiac arrest. In the days that followed, that shoe kept coming to mind. At home, I kept looking for it subconsciously. Ultimately, I ended up asking my mother if she had seen it. She told me that most probably it had been disposed off. Before throwing it, my dad had taken that picture and sent it to me. So the picture was all I had for the moment. A few days later, there was a storm. As it started raining, I ran upstairs to retrieve the clothes that had been hung out to dry. The rain smelled different. The leaves of the vine danced and tried to shake themselves free but were subdued by the heavy drops. Something made me look closer at the base of the terrace where a few odd trinkets were always kept and there it was, my old doll’s shoe, all cleaned up. I don’t even remember the doll it belonged to. I don’t remember so many things about my childhood. All of it nestled inside my father’s heart that I was not careful with when it was still beating. All I could do was hold on to the shoe that my father was unable to throw away.

Every time I look at my mother’s closet, my heart breaks. She has a note there, pasted on top. “Ruhi and Noor are happy and doing well. Chanchal and Ruhi are happy and well.” Her notebook is filled with her prayers for us. She wonders why god did what he did. I doubt there is a god. And believe me, it is a kindness when I say so. Which god would want to take the blame for all the pain in the world? I would rather think of natural forces and their arbitrary fury. Does an earthquake analyze the religious beliefs and good deeds of people before striking? Do I look at an ant’s life’s work before stepping on it? It is simpler for me to make sense of things this way. One continues to do good not out of fear or for the rewards to come. The gift comes with the deed, in that moment. The punishment of doing bad too comes with it. The heaviness that settles within your heart, making it darker.

For me, religion was not god but looking at my mother and father from the side as I placed my head on the carpeted floor to bow, it was cuddling next to my mother and then hopping away to my father as they sat in the Gurudwara, it was walking together on the cool marble floor warmed slightly by the winter sun, it was placing the piping hot parshad in my dad’s hands till it cooled down. It was the fragrance of besan and alsi that smelt like my parents’ affection for each other and for us, wafting through the kitchen as they both stirred the pots, adding almonds, making round ladoos with their cosy hands. Even when I went to hostel, they always sent a big box for me for the winters.

My father lived entirely in the present. Always. He was always aware that life was short. That the present was all we had. And that is how he lived. But for me, I feel that my life has wrapped itself up in the past.

I feel like a multistoried house shaken to its core by the earthquake. Every day since that day, one of my room collapses. A room I did not know existed. It’s almost as if pain is taking me on a tour in my recesses. Showing me. This. This hurts. Look here, this here hurts too. Because it was real. There was love. It happened. Do you remember that time when? He was there. He is still here but not in that same way, you see? He won’t answer back. No new dad jokes. No new bad selfies. Those stern hugs that never failed to reassure me while putting me back on my feet over and over again. The way my sobs ebbed away while hugging him till I was calm like a lake. I try to imagine him back into existence. In some ways, he feels even more real now. Closer too.

My entire life seems to have been forever divided into before and after. Nothing changed on the surface. But everything changed from the inside. A world has been put to sleep inside me forever. A new one is awake now. A world that lives to self-destruct. Looking at the storm, hearing the thunder, feeling an earthquake seem closest to the new normal. It is the regular days that scare me the most. When the world continues to move on. The way I continue to eat, sleep, work and laugh. This is the actual horror story. My mother, father, brother and I were more or less the same person. I sometimes feel like we died too and this is another lifetime. I am afraid of all that spiritual bullshit. How everything becomes one. How the hell am I supposed to find him later if everything becomes one? I better be reunited with him when I die or rather get switched off completely. Till then, I want him to live through me.

I want to believe he is here, around me.

I have been reading a lot about near death experiences to learn more about death. After all, one of the people I love recently moved to that world. So of course I am invested. I want to know if he is safe and happy and at peace still. I can’t help it. For all the skepticism, I want to fervently believe. I have convinced myself that I can will him to exist. That I can create my own sense of time, reality, in my mind. That time and space can be what I want them to be, inside my mind. But I am not always so clear-headed. More often than not, I am like a baby, crying for things to be otherwise, stamping my feet, hitting my head against a wall that refuses to give way to sense and meaning. Death feels so absurd. His absence makes no sense to me. For someone who loved life so much. Our small little world. We were too ordinary. Too unremarkable. Too non-serious. For something like this to happen. You see what I mean? The things we were joking about only a few days back. It makes no sense when I lay those down next to what happened.

I think I romanticized death a lot before. Rationalized it a lot too. In reality, it is not a concept. It is far too personal. I can’t even call it death. I don’t know how to explain it except that my animal mind is losing its shit. I feel like a mouse caught in a trap. I am panicking daily. I can’t understand that the clenching of my hands and teeth, that nervous feeling in the pit of my stomach in the evenings are there because dad is being awfully silent, awfully missing from conversations, awfully absent from backgrounds, no longer seen or heard around the house. I am unable to send things to him, feed him anything, watch a new movie with him, introduce him to anyone new, tell him about anything that happened today. He is no longer answering his phone, using any of his things. No longer annoying me. He is not helping us in any moments of crisis which seems so unlike him.

People come and go. Language languishes in the corner. Their words float over my skull like fruit flies. My mind is like a completed jig saw puzzle board that caught fire right before the last piece was placed— What the actual fuck?! Language does not move me anymore. I keep words at an arm’s length. Even now. I feel the uselessness of this. Except that through this, I am trying to make sense. Knowing fully well there is nothing to grab, no meaning, no fire to be made here, and no solace. It is ridiculous really. All this for what? Time will heal. What a bitch. Biology is no shit. You cannot mess with the science of the mind. All this romanticizing of life and death. Let’s make all his dreams come true. How am I supposed to disentangle my dreams from his? You have to live for your mother, your mother has to live for you. What a trap! Is there any meaning to this?

There are no answers here. No matter how hard my heart cries out. My voice is met with silence. Endless void.

I am scared of walking down the same paths through the woods. Looking at the berries he loved to pluck out and eat. Every tree, every branch will forever ring with his absence. The last song he sang minutes before leaving us continues to echo in my ears.

I think of this world as a waiting room now. I can be called at any time. Anyone around me can be called. At any time. There truly is no guarantee. What will I spend my time doing till I am called? That is all there is now. There are so many lasts that have already happened. Many lasts are happening every day. A street I will never walk on again. Things I have looked at the last time without knowing. No one knows.

It is better not to know I guess.

When I miss him so much that I can’t breathe, there is a place in my mind I always try to go to. A beautiful moment stolen from a beautifully ordinary day. In the memory, I cannot see my dad. I cannot see anything. In fact, my eyes are closed, my head on the bench. I am taking an afternoon nap outdoors. I cannot see my dad but he is there, sitting by my side, sketching the scene in front of him. The undulating hill, the road below, and the beach segueing into the gleaming blue sea. I can hear the seagulls, excited voices, cars going by, and the sound of my father’s pencil softly grazing the paper. We do not say a word. But we both know we are together.

There is a highway bridge of my dreams. The light of the scene is blue. Two people stand there in the middle, staring at the dark waters. They stand with their backs to one another. The stream flows from one to the other. Though they cannot see one another at the moment, they have never been more aware that they are not alone.

Only now I am beginning to understand the things I wrote long back. How strange is that?

My mind is real. My memories more real than the present. I know I can will him into existence.

I don’t believe in god but I do believe in love.

I know I have my father’s hands and my father’s eyes. Sometimes when I am cleaning the car in the morning, sunlight glints through the branches of the mango tree, its leaves fluttering in the breeze. It always makes me pause and look up. The blossoms keep falling. The birds keep chirruping. I whisper under my breath—

Here is the world, dad. Here is life. Look.

Leave a reply to Monika Sharma Cancel reply