13/4/2020

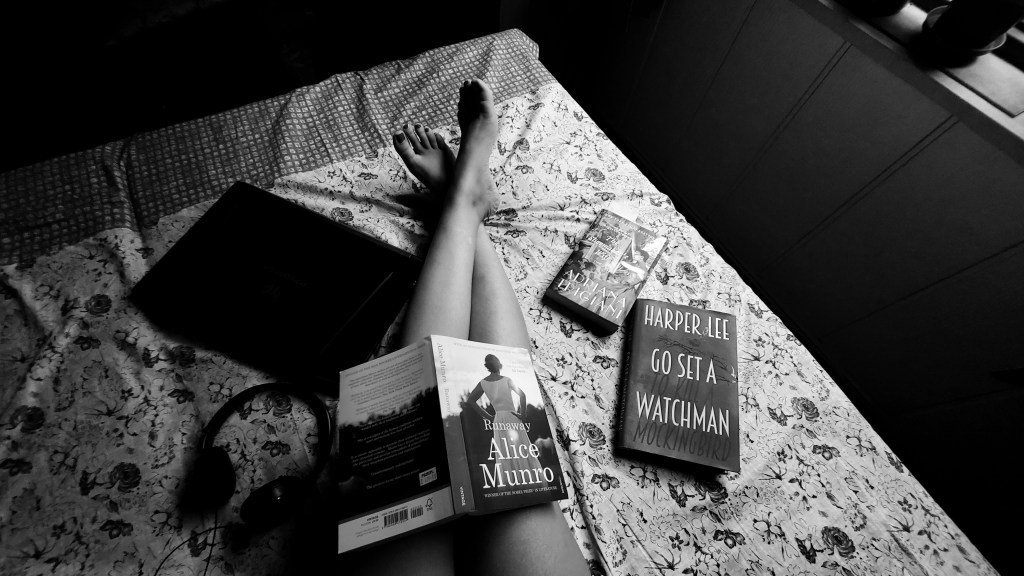

Last night as I was reading Runaway by Munro, I happened to eavesdrop on one of the characters. She, in turn, had been reading about kings and queens who were turned into constellations for being too arrogant or beautiful. Together we thought of the gods getting jealous of those that shone with a fire too bright for this world, turning them into examples, into distant objects of our admiration, hanging them onto the skies above our heads.

These days in the evening we go to the roof of our house for our evening walk, since it is not really safe to go outside anymore. As you already know, outside is where an invisible apocalyptic reality awaits. My mother is usually on her phone. She attends her work related calls there. When she’s not doing that, she jumps like a cat over to the roof of a neighboring shop to look at the people passing by on the road. I tell on her to dad and he just smiles and lets her be. Dad usually brings his wireless radio upstairs with him. Sometimes it’s not charged and a woman’s automated voice starts interrupting the songs. And I have absolutely no idea whatsoever as to what she is saying, or the language in which she says it. It’s a daily ritual. I usually carry a Munro book along, to read. I walk and read. I find it really stimulating. And I like the evening light falling on the pages of my books. It’s not the stark sunlight of the afternoons, but softer, more gently luminescent. Everything that I read appears so much more profound in that light. I go around in circles by the mango tree that has grown tall enough to reach our roof. Often, I pause to take countless futile pictures of the sky and the growing mangoes that I fill mum’s phone with. Nothing gets captured the way I want it. Then as the sky turns blue and it gets darker, I place the bookmark where I left off and close my book. It is around seven in the evening these days when the twilight spreads across the sky and it is time for the evening news on the radio which is usually about the virus. Sometimes I listen, sometimes I don’t. The evening star appears and another ritual is performed. I have no idea how it started. I think it was my mum’s idea. Every day she asks us all to say a little prayer of gratefulness to this constant star, thanking it for another day spent safely. And we all do. Somehow when I see it, I cannot see it. When I don’t see it, I can feel it more. So I look back at it, startled for not having paid enough heed to it and it is right there, a little speck of light. I feel slightly disappointed with things I can see. I take them for granted I guess.

In any case, Venus is known to absorb the ill tempers of the more mercurial forces in the universe. Being benign, I wonder how she looks upon us. Probably, she is already sick of Mars throwing his tantrums all over space. How long before Venus has had enough? Or is her capacity to absorb the heated violence around her infinite?

There is this story of the eagle I keep asking my dad to narrate over and over again, simply because he hates to. During the lockdown, since he could not escape me, I must have asked him to tell this story a hundred times by now.

Once upon a time, an eagle flew into my dad’s house. I don’t understand exactly where it landed or how. Even though I heard this story so many times, I am still pretty confused. He calls the exact place the ‘padchatti‘. It sounds like something I have a vague understanding of but don’t understand well enough to define it for you. Anyways, this was from before he had married mum, or we would know who would have to take care of it right away. Every time a wild creature is found in our house (for us, a wild creature would mean a rat, a mouse or a wasp), I am the first one to jump onto a chair or a bed or hide behind the curtains and dad is the first one to demand the creature’s swift banishment from our kingdom while slowly sneaking away from it. There is only one warrior who can fight these stranger beings. And that is my mother. And she comes with a broom or in case of wasps, covers herself from head to foot, marching like a fighter straight out of Star Wars with her helmet and gloves. But in any case, when the eagle got stuck at ‘that place I do not know of’ and would not leave, dad was still a bachelor and mom, who had not yet met him, could not come to the rescue in her avatar. So, he had on his hands an eagle that had somehow got trapped indoors. And on top of that, it was sick and retching. This probably had to do with the fact that somehow, it could not find its way out. Anyways, it smelt really horrible in there. That is what my dad recalls when he thinks about it. In the end, it was my grandmother who came in with a ‘dang’ (a wooden stick) and urged the eagle to fly away from the window. Somehow, I am unable to imagine a grand creature like an eagle being indoors in a congested space built by humans. It was made to roam the high skies. It fascinated me to think of such a big bird and its wonderful expanse. I was glad and relieved when every time during yet another narration, it found its way out and flew away. And I was curious about something else. I wanted to know what it felt like, looking at it in the eye? When I asked dad to describe it to me, he said it was ‘big’. That was it. He wouldn’t tell me how big or what its eyes looked like either. I guess he was too overcome by the smell. In any case, he said, if I had been there, I would not exactly be ‘fascinated’.

15/4/2020

Every time I read Munro, I am wonderfully disturbed. I asked my mum once, what do you do when you read something that you resist but know to be true? She said I never thought about it much. And I wondered how blissful that must be, to be so preoccupied with the act of love, work, life, happiness, to not have such thoughts. But reading Munro- well- it is like, every time her heroine is on the verge of taking any step, I hold my breath and pray for her to not do it, to stay the way she is, to be safe, discontent but safe, to avoid a disaster. But she ventures forth anyway and I know she would still be discontent. And I wonder, did I? Did I venture forth? Why am I so afraid? Did something go wrong? No. That is not the question. What bothers me is, did I venture forth, if at all? And if so, when?

There is this particular part of the terrace at my house from where, if you look down, you can see the street through a frame of the mango trees, the loquat tree and the crisscrossing street wires. But the banisters are really shallow and so it is kind of a risky business. This was the very reason because of which my brother wasn’t allowed to fly kites on the terrace, though he badly wanted to. This is the spot where my mother, sometimes my dad, and sometimes I, go to peek and strangely every time one of us does so, the others pull him/her back by the arm or at least there is a verbal warning shouted from behind. It’s out of love and fear. And it made me think, how for safety and security, a family becomes that force that won’t let you venture out into those terrains, or even into a dangerous adventure of any sort. This used to happen every time I was near water. I badly wanted to go closer, an almost primitive need. I wanted to walk down the fairie roads of Scotland which were supposed to be haunted, but my mother would not allow it. Be safe and safe. Be safe. Have regrets, of not knowing, but be safe. A strange fury would take hold of my mother as she would pull me back, going as far as lashing out personal comments on how I couldn’t stay put, with everyone else and always had to venture forth on my own. Why was there this need of being isolated and hence being somewhat ‘special’ stuck in my head? Could I not enjoy with my family, like everyone else? Strangely, this need to venture out was in her too. I seemed to have bequeathed it. But years later I found myself saying the same things to those I loved. Be safe, come back.

But what happens if you are on your own? Is that preferable? Not at all. Read this excerpt from Munro’s Open Secrets (and I’ll be quoting a bit of it today). It is about this Canadian woman who is exasperated with her traveling companions who are all middle aged and easily alarmed:

After dinner they walked on the terrace but Mrs. Cozzens was afraid of the chill, so they went indoors and played cards. There was rain in the night. She woke up and listened to the rain and was full of disappointment, which gave rise to a loathing for these middle-aged people… These people ate too much and then they had to take pills. And they worried about being in strange places- what had they come for? In the morning she would have to get back on the boat with them or they would make a fuss. She would never take the road over the mountains to Cetinge, Montenegro’s capital city- they had been told that it was not wise. She would never see the bell tower where the heads of Turks used to hang, or the plane tree under which the Poet Prince held audience with the people.

Alice Munro

The next excerpt is from when her guide gets attacked by the tribe of a kula and she is herself taken in by them as she is injured and she thinks about how her absence would not be even registered:

No doubt there was some sort of search for her, after the guide’s body was found. The authorities must have been notified- whoever the authorities were. The boat must have sailed on time, her friends must have gone with it. The hotel has not taken their passports. Nobody back in Canada would think of investigating. She was not writing regularly to anyone, she had had a falling-out with her brother, her parents were dead.

Alice Munro

I read these lines and I can sense the panic rising in me for the character. No one calling you, worrying about you anymore. Even the thought of it is scary. Its natural isn’t it? We want someone to worry about us too. In Munro’s other book (Runaway), I was reading about how Juliet’s daughter Penelope goes to a retreat one day and the wait of a few days turns into weeks, weeks into months and then to years till Juliet feels like the Penelope she knew does not exist. She gets to know about her daughter indirectly from her daughter’s friend who unleashes information about her daughter on her nonchalantly, because she doesn’t know the rift between the two. And Juliet finds out that her daughter already has three kids and she was seen in a mall, unrecognizable, to get uniforms stitched for her children. I was horrified to read this. My mind cannot, by the biggest leaps of imagination, imagine such a situation. What was that big blunder that Juliet had committed for Penelope to be so unforgiving? Maybe it was some buried grief. Dysfunctional relationships. I don’t know. My Indian mind cannot comprehend. And yeah, it was at that moment when I realized how being born in a certain place can change you completely and leave its imprints. Indian families do tend to stick together, sometimes beautifully, sometimes in toxic ways. But they do. And in times of crisis, they stick together even more. I think of this as we sit together, eating mangoes. Outside, the skies continue to darken as the world inevitably ventures forth for a tryst with the morbid unknown.

Leave a comment